2 Constructive Alignment

Sharon Bal; Kelly N. Roszczynialski; and Teresa M. Chan

Authors: Sharon Bal, MD, CCFP, FCFP; Kelly N. Roszczynialski MD, MS

Editor: Teresa M. Chan, MD, FRCPC, MHPE, DRCPSC

A Case

Claudia has just become a new pre-clerkship curriculum coordinator for a prominent medical school. The program is currently undergoing curriculum renewal, and she has been tasked to advise on pedagogy that will ensure optimal student engagement and deep learning. She is provided a list of learning objectives that need to be covered throughout the pre-clerkship, as well as a document indicating “where and when” in the curriculum each topic is taught in the first two years. She is told that the medical school strategy is to modernize the curriculum as they move away from largely didactic teaching, but are not clear on where they want to land.

Claudia was just considering this project when she gets a call from a former medical school classmate, Michelle, reminiscing about their trials and tribulations of undergraduate medicine.

Remember when we just gave up studying and learned to memorize old tests? Man, I wished I’d known back then that CribNotes is all I needed for clerkship, I would have had so much less stress. It was like all the surgeons took their pimping questions straight from the book…

Claudia’s amusement quickly changes to chagrin as she realizes, her scope involves not just considering learning theory, but also providing instructions as to how best to align current curricular components such as assessment to ensure defined learning outcomes. She is cognizant that medicine is no longer simply about transmission of a body of knowledge, but about acquiring the skills to problem-solve and address gaps. She will need to consider these learning outcomes, and recommend the teaching activities and assessments that indicate success…wow, this was going to be a challenge!

Background

Medical education since the turn of the last century was rooted in the reductionist, biomedical model of medicine itself. It was this tradition of hierarchy that determined that the role of teacher (mirroring that of physician) was, to a large extent, that of omniscient content expert. There was a large, but somewhat finite lexicon and inventory of factual knowledge, which learners were expected to master during their studies in medical school and subsequent training. The role of learner was, in this respect, more passive and the teacher’s role was to transmit this body of knowledge to the student.3

In recent years, educational theories based in cognitive learning theory4 in support of active learning and less hierarchical paradigms have grown increasingly the norm in medical education. In constructivist alignment theory, the role of the teacher changes4 from transmitting knowledge to assisting learners in their own critical self-reflection. And, similarly, the locus of learning for the student has gone from an external to an internal one. The emphasis on the experiences and meaning in the construction of knowledge further moves away from the generalism of the didactic or traditional curricular design by acknowledging individuality in knowledge acquisition. It is the latter that makes the “alignment” of appropriate teaching activities to ensure student engagement, along with appropriate assessment tools, key to achieving the intended learning outcomes1,2 (ILOs). Modern takes on this Theory. Another key component of this theory, as described by Biggs in his 1996 article, is that constructive alignment comprises a whole learning system, which embraces “classroom, departmental and institutional levels.” He contrasts CA with poorly designed systems in which curricular components such as teaching and assessment are not integrated as a unified process. For example, a psychiatry course on critical analysis that uses multiple choice tests as a final assessment, which does not test the students ability to display their logic or thought process. In fact, essential to CA is the outcomes-based approach2 to teaching, the ILOs then define both the instruction and assessment. In this way, CA itself requires significant investment and energy to fully implement the learning environments, by starting with what we want students to know by defining the intended learning outcomes, we then align teaching and learning activities, and assessment plans.

Intended learning outcomes differ from traditional learning objectives in that they are demonstrable and focus on application and higher level learning as opposed to focusing on discrete knowledge that is being taught. ILOs must be written in such a way that they can be observed and measurable in order to appropriately align later with planned assessment. When determining the needed teaching and learning activities a distinction should be recognized, with a student centered approach, teaching is input while learning is output. Learning activities may include traditional direct instruction, readings, lectures, or assignments that can serve as both a learning method or a mode of assessment to ensure learning has been mastered. These activities may include simulations, case studies, presentations, lab work, or problem based learning.

Overview

“Constructive alignment” can be broken down into two components. The first is based on constructivism, the idea that learners construct their knowledge from learning activities that they can integrate and build upon their current belief system (meaning) and prior experience. Knowledge is not directly passed from teacher to learner, rather the learners must engage and create new meaning for themselves. The second component is alignment: the objectives, teaching activities, and assessment that support the learning. The intended learning outcomes are the driving force to then determine appropriate assessment strategy and finally align the teaching activities to the intended outcomes as well as the assessment tool.

Constructive alignment (CA) differs from the theory of criterion-referenced assessment which aligns assessment to objectives in that it also includes aligning the teaching methods with the focus on intended learning outcomes (ILOs). The goal of constructive alignment is to support students in developing meaning and learning from a considered, well-designed and aligned course.

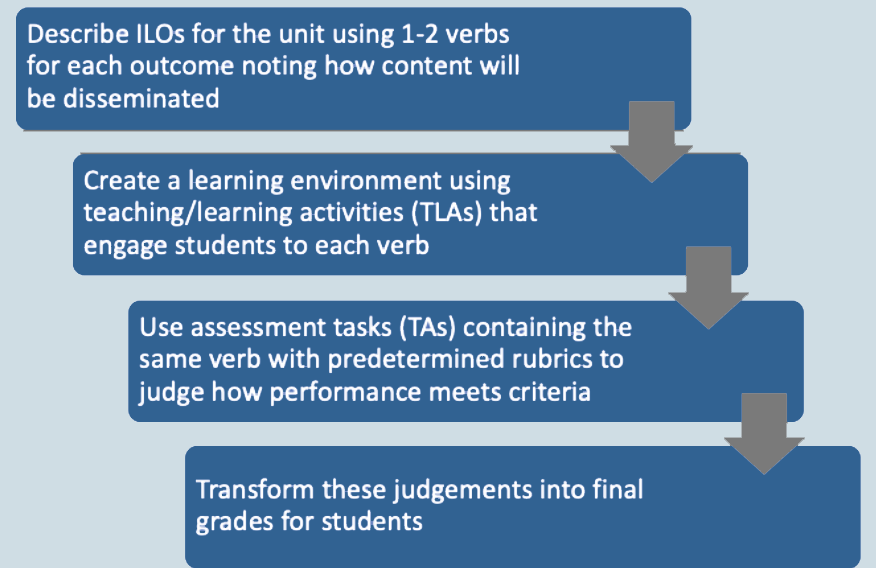

In constructive alignment, as described by originator Biggs1, one must consider teaching and learning to be a whole system2:

Main Originators of the Theory

John B. Biggs

Other important authors or works:

Catherine Tang

Modern takes or advances in this theory

Outcome based medical education echos constructive alignment theory, by orienting training on intended learning outcomes. As described by Biggs and Tang (2011), in outcomes-based teaching the question changes from which topics are taught to “What do I want my students to be able to do” after curriculum completion2. Medical schools have begun implementing such learning activities as problem based learning sessions, portfolio education exercises, and narrative exercises into undergraduate medical education. Medical simulation has become increasingly integrated into medical education at both undergraduate, graduate, and post-graduate continuing education levels and can serve as both a learning activity with team based learning or for assessment such as OSCEs for undergraduate medical education.

In more recent times of crises during the COVID-19 pandemic a need surged for education on management practices and personal protective practices across the world. Institutions have used this same framework to first identify the learning outcomes of safe care for potential COVID-19 patients, developed quickly implemented learning activities through teleconferences, discussions, and simulations to align for assessment of these critical skills. Assessment in some settings includes auditing by Infection Protection and Control (IPAC) experts.

Other Examples of Where this Theory Might Apply

It is important to remember when designing intended learning outcomes the three domains of learning: cognitive, affective, and psychomotor. The classroom setting may be more applicable to cognitive learning outcomes such as students will be able to analyze the impact of socioeconomic status in rural medicine. Similarly this could be designed for the affective learning domain and written as students differentiate medical care received by patients of lower socioeconomic status in rural settings. Narrative exercises could be incorporated from both ILO domains and assessment may include case studies in the classroom setting or field work during a clinical rural medicine rotation.

Another application for constructive alignment in the clinical setting is in procedural training6. One common intended learning outcome in the postgraduate medical education and training is safe and effective central line placement for the critically ill patient. Other medical education theories and modalities, such as medical simulation and mastery learning can serve as excellent teaching and learning activities and have paired assessment with mastery learning checklist and rubric/criterion levels for evaluation.

Limitations of this Theory

Not all of medical education takes place with a curricular design plan or in a controlled classroom setting. In particular, the clinical rotations in medical education have a different structure for both the teacher and the learner. While the overall clinical clerkship course may allow for an overarching curricular plan, the daily “in and out” of clinical rotations limit the reach of constructive alignment educational theory. The variety and diversity of patient presentations during clinical rotations is often what inspires teaching topics and these change on a daily basis. Because of this inherent design of the clinical rotations the forethought and planning that are required for constructive alignment may not fit for every learning environment.5,6 Constructive alignment requires significant energy for appropriate reflection1,3 and preparation to develop the intended learning outcomes, design the associated teaching and learning activities, and create aligned assessment. This makes constructive alignment a difficult modality to employ on an immediate basis.

Returning to the case…

After a significant amount of research, and consultation with learners and faculty colleagues, Claudia feels that the best approach to ensuring deep learner engagement and achievement of intended learning outcomes (ILOs), would be basing the curriculum renewal in constructivist alignment theory. In presenting to the medical school’s curriculum committee, Claudia references the work done by Biggs, and how intentional consideration of teaching activities and assessment will ensure achievement of medical education objectives.

Claudia finds an apt audience as she walks through the ways in which constructive alignment could apply to diverse instructional activities, including problem-based learning (PBL) tutorials, portfolio education exercises as well as clinical activities. She describes Biggs’ distinction between declarative knowledge, and how this kind of tradition best reflects her own undergraduate education, versus functioning knowledge. It is this latter, deeper knowledge acquisition in our learners that should be our ultimate aim in designing curriculum. Construction of knowledge, which is anchored in both experience and meaning, is key for deep learning and the independent, learner-driven creative problem-solving that the modern student requires in the ever-changing landscape of modern medicine. The teacher’s task now becomes fostering the engagement in the material to ensure students can use their knowledge – making it functional – and of use to them in their practice and increasing their confidence.4 She emphasized that alignment of curriculum includes assessment tools to ensure objectives will be met.

She reflects on how different the incoming medical students’ experience might be from her own, and can not help but pick up the phone to brag a little to her classmate!

References

- Biggs, JB. Aligning teaching for constructing learning. Higher Education Academy. 2003. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/John_Biggs3/publication/255583992_Aligning_Teaching_for_Constructing_Learning/links/5406ffe70cf2bba34c1e8153.pdf. Accessed: May 15, 2020.

- Biggs, JB. Constructive alignment in university teaching HERDSA Review of Higher Education, vol. 1.

- Biggs, J., & Tang, C. (2011). Train-the-Trainers: Implementing Outcomes-Based Teaching and Learning in Malaysian Higher Education.

- M Robinson, H Murray. What Can Cognitive Learning Theory Teach Us About Effective Teacher Behaviours. REFLECTIONS 1992

- Joseph, Sundari & Juwah, Charles. (2011). Using constructive alignment theory to develop nursing skills curricula. Nurse education in practice. 12. 52-9. 10.1016/j.nepr.2011.05.007.

- Loretta M Jervis & Les Jervis (2005) What is the Constructivism in Constructive Alignment?, Bioscience Education,6:1, 1-14, DOI: 10.3108/beej.2005.06000006

- Barrow M, McKimm J, Samarasekera DD. Strategies for planning and designing medical curricula and clinical teaching. South East Asian Journal of Medical Education. 2010;4(1):2-8.

Annotated Bibliography

1. Biggs, JB. Aligning teaching for constructing learning. Higher Education Academy. 2003. Original Theory

This summary is written by the originator of the theory itself, John Biggs, and reviews the two key aspects of constructive alignment. It reviews the overarching steps to align intended learning outcomes, teaching/learning activities, and assessments to create a global high-level learning system.

2. Loretta M Jervis & Les Jervis (2005) What is the Constructivism in Constructive Alignment?, Bioscience Education, 6:1, 1-14, DOI: 10.3108/beej.2005.06000006

In this paper the authors describe constructive alignment specifically focused from the constructivism perspective. They comment on the wide definition of constructivism and how its broad applicability has led to confusion particularly in science education where there is a need to distinguish realism as a knowledge theory from constructivism as a learning theory. They critically evaluate the application and limitations of constructive alignment and argue against its use in scientific education.

3. Biggs, J., & Tang, C. (2011). Train-the-Trainers: Implementing Outcomes-Based Teaching and Learning in Malaysian Higher Education.

In this paper, the authors responsible for describing constructivist alignment (Biggs) and the more detailed implementation of this theory (Biggs and Tang) review its implementation in Malaysian higher education using the Train-the-Trainer model. In reviewing this model, they review quantifying the level of understanding being sought when stating the intended learning outcomes, distinguishing between declarative and functional knowledge, and state that while much of university teaching is focused on the former (declarative) knowledge, what is required by practitioners is the functional type as their knowledge needs to inform action. Matching the ILOs, and subsequently the teaching and assessment methods to the knowledge type is imperative. The trainers, also, must understand constructive alignment such that principles are applied as intended.

4. Barrow M, McKimm J, and Samarasekera DD. Strategies for planning and designing medical curricula and clinical teaching. Medical education in Practice. South-East Asian Journal of Medical Education. 2010;4(1):2-8.

A brief review of curriculum developments in medical education discussing the practical application of constructive alignment and the shift towards learner-centeredness. A case example of the Yong Soo Lin School of Medicine revised five year undergraduate medical education is provided, showing the practice of the theory and inclusion of teaching and learning activities such as simulation, problem based learning, and team based learning. They also briefly address the gap that can exist between the clinicians teaching in the clinical setting and those designing the curriculum, highlighting the need to specifically design learning outcomes to be applicable to the variable clinical setting.