7 Logic Model of Program Evaluation

Kathryn Fisher; Jeanne Macleod; Sarah Kennedy; Benjamin Schnapp; and Teresa M. Chan

Authors: Kathryn Fisher, MD, MS; Jeanne Macleod, MD; Sarah Kennedy, MD

Editors: Benjamin Schnapp, MD, MEd; Teresa Chan, MD, MHPE

A Case

Sarah has just finished her ultrasound fellowship and is working at a new hospital in the Emergency Department. She has discovered that many of her new partners are not familiar with or comfortable using bedside ultrasound in clinical practice. When she inquires about this, many of her coworkers mention that they were educated prior to 2006, when ultrasound became incorporated into residency training as part of the required curriculum for residents.

Sarah would like to design a certification program for her colleagues to help them become more comfortable with performing and interpreting ultrasound in clinical practice. She would like to develop a curriculum initially with some core ultrasound applications to teach her colleagues how to perform and interpret basic bedside ultrasound studies and then expand to other imaging applications. How can the Logic Model of Program Evaluation help her design a program? What activities can be planned and what outcomes could be measured to ensure success of her program?

Overview

The logic model is a conceptual tool that can be used when facilitating program planning, implementation, and evaluation. This tool is designed to examine a program’s resources, planned activities, and proposed changes or goals in an organized fashion. It describes the linkages between resources, activities, outputs, outcomes, and their impact on the program as a whole. It provides a model of how a program might function under certain situations.1

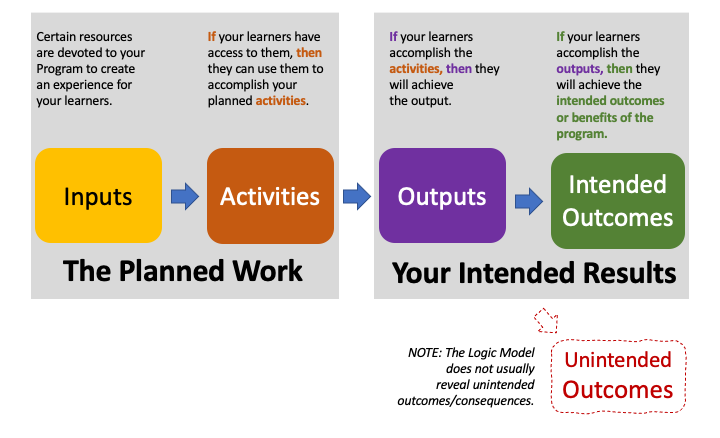

The logic model is represented visually in four main sequential components including inputs, activities, outputs, and outcomes. These comprise two main domains: planned work and intended outcomes. Planned work includes inputs and activities while intended outcomes reflect the outputs and outcomes. Outcomes can be measured as immediate, intermediate, and long-term. Some sources also suggest a fifth component, a measurement of impact, at the end of the model in lieu of, or in addition to, long-term outcomes.2 In business applications, many logic models also contain a schematic of external influences as arrows into each of the components to show how each of these external factors affects each of the steps of the model.

This model has been used in initial program design and planning, in program evaluation and restructuring, and for other individual or group evaluative processes. It provides a structured framework to systematically evaluate program components and to communicate with team members. The logic model is a tool applied to facilitate acquisition of the information necessary in decision making as it relates to evaluation and restructuring. The logic model is specifically useful in determining evaluation for medical education programs.3 Figure 1 below depicts the workflow of a typical logic model where a program’s intended inputs are linked to the program activities, and then to the program outputs, which should result in the intended outcomes. In the figure below, we depict how the unintended outcomes are not usually measured by the logic model, which focuses on the intended outcomes.

Main Originators of the Theory

Edward A. Schuman

Joseph S. Wholey

Background

The early ideas of logic models were first raised in a 1967 book by Edward A. Schuman about evaluative research.5 Over the next decade, two types of logic models emerged. One called Theory of Change and the other termed Program Evaluation or Outcomes Model. The Theory of Change model is more conceptual and provided the foundation for the Program Evaluation Model, which is more operational.4

The concept of a logic model was previously captured in other structures and under different variations including “Chains of Reasoning,” “Theory of Action,” and “Performance Framework.”1 Bickman 1987 introduced logic models as a tool for program evaluation that emphasized program theory.6

The first publication using the term “Logic Model” was by Joseph S. Wholey (1983).7 McLaughlin and Jordan3 were also champions of the logic model approach. The first developers of the logic model came from business, public sectors, international non-profit sectors, and other program evaluators. Logic models did not become widely used until the United Way published Measuring Program Outcomes in 1996.8 This article was important in establishing the terms and structure used today for developing Logic Models. The W.K Kellogg Foundation published a widely available Logic Model Development Guide which has been used for public policy and healthcare planning.9 Over the last decade logic models have also been used for medical education program evaluation.

Inputs can be seen as certain resources necessary to operate the program.3 Inputs include resources dedicated to or consumed by the program and can include financial resources and funding, protected time for faculty or staff, expertise of faculty and staff, administrative support, and physical resources such as facilities and equipment.

If a program has access to inputs, then it can use them to operate planned activities.3 Activities represent what the program does with the inputs it has to fulfill its mission. Activities may include any combination of needs assessments, teaching, curriculum design, planning of sessions, faculty development, development of systems, or performance evaluations. These activities are dependent on the program’s mission.

If the planned activities are accomplished, then the program will deliver the intended product or service output.3 The outputs section in logic models describes the direct, measurable outputs of the activities. This can include demographics such as number of participants in a program’s activities, number who completed a certain curriculum, or program metrics such as number of programs, time in existence, or number of graduates of a program.

If the planned activities are accomplished to the extent represented in the outcomes, then the organization will be affected in certain ways as described by the outcomes.3 Outcomes can be measured immediately, as well as in the intermediate and long-term time frames and are generally split into these time designations. They look at the benefits for participants during and after program activities. These can include increased knowledge or skill, satisfaction with quality of activities, or improvement in evaluations. Additionally, outcomes can be measured by various metrics dependent on the program for clinical, teaching, program, or academic success following the implementation of activities. Awards, productivity, shared resources, and increased involvement can also be measurable outcomes.

Finally, if the benefits of the program are achieved then the activities implemented as part of the program will have an impact on external factors such as an organization or system.3 This can relate to impact on an industry or system based or impact it has on the community, environment, or infrastructure.

Modern takes on this Theory

The Logic Model is a tool that can facilitate communication and can be used for idea sharing, identifying projects critical to goal attainment. The logic model can identify if there are implausible linkages among program elements or redundant pieces.1 Benefits of the logic model include gaining a common understanding and expectations of resources, their allocation, and results. In the past few decades, the logic model has been applied to various applications in medical education and healthcare. Generally, the model is most widely used for innovations and new program design or in evaluation of current programs. Program managers are using the logic model to argue how or why the program is meeting a specific customer need, whether that customer is in a private sector or the customer is a medical learner.1 In a more cognitive sense, the logic model is used to facilitate the process of thinking through faculty development and other large-scale initiatives.3 Other uses have been adopted on a larger system scale for healthcare systems innovations.1 They have also been used on a larger scale in the public health workforce to support ongoing program planning and evaluation and for communication between divisions.10 Portfolio evaluation, or the evaluation of multiple projects with a common purpose, also benefits from the use of logic modeling as a visual tool.11

Logic models have been used as a way to determine consensus among leadership or with stakeholders in a certain situation, as one can examine both the inputs and the desired outcomes and how they will be measured. This approach can be applied to medical education in the setting of institutional self-review.12 The World Federation for Medical Education utilized a logic model applied to further define and evaluate each of their accreditation standards. In this specific case, the logic model was used both for standard setting and consensus of their standards, but also as an evaluative tool.12

Other Examples of Where this Theory Might Apply

Van Melle et al proposed how to use the Logic Model in Program Evaluation for Competency-Based Medical Education (CBME).13-15 The authors provide an outline of how to use a logic model to focus CBME program evaluation, how to make a program evaluation scholarly, and how to build capacity for program evaluation. They used the Logic Model framework to provide an outline on how to evaluate CBME initiatives in a residency program. This is broken down into a flow chart of an Outcomes Logic Model. First step being the Purpose of CBME, then resources to implement (Inputs), followed by what Activities are critical for CBME. The final step is that the program results are broken down into Outputs: the description of competencies and Outcomes: proximal and distal. The proximal outcome being enhanced readiness for practice and the distal outcome being improved patient care.16

Limitations of this Theory

The Logic Model’s main limitation is that it may lead to over-simplification and miss many of the unintended consequences because of its focus on the program’s desired outcomes. Medical educational programs are often complex and don’t always follow a linear path. To overcome this limitation the Logic Model needs to be well designed. The creators of the model should have a thorough understanding of how change works in the educational program being evaluated. Both intended and unintended outcomes should be anticipated, and feedback loops must be incorporated into the model to address these complexities. The Logic Model design needs to be flexible and dynamic in order to integrate unexpected complexities. Educators and researchers need to be prepared to revise the model as the program is being implemented. Therefore, the development and revision of a logic model can be a time-consuming process.

Complexity can be built into the Logic Model by the addition of multiple tiers. Mills et al attempt to address this problem in their 2019 article.10 The authors propose a typology of logic models. They categorize logic models into four types, ranging from simple (type 1) to the most complex (type 4). The type 4 logic models attempt to provide more insight into the interactions between interventions and context (social, political or cultural factors in the environment where the program exists).

The greatest challenge is to find the balance between precision, which may require many data points, with the creation of a concise, easy to understand model.

Returning to the case…

Sarah uses the Logic Model to plan a curriculum for her coworkers to obtain initially core and then global ultrasound certification in a step-wise approach. See Figure 2 for a diagram of her logic model. She creates a pre-survey and pre-test to see initial attitudes and knowledge. She then creates educational opportunities to teach her coworkers. She has a post-survey and post-test to evaluate how behaviors, knowledge, and attitudes have changed over the course of a year. Sarah makes a goal of certifying 75% of her colleagues in core ultrasound applications and then expands her program to include other imaging applications.

References:

- McLaughlin, J.A. and G.B. Jordan, Logic models: a tool for telling your programs performance story. Evaluation and Program Planning, 1999. 22(1): p. 65-72.

- Developing a Logic Model or Theory of Change. [cited 2020 May 22]; Available from: https://ctb.ku.edu/en/table-of-contents/overview/models-for-community-health-and-development/logic-model-development/main.

- Otto, A.K., K. Novielli, and P.S. Morahan, Implementing the logic model for measuring the value of faculty affairs activities. Acad Med, 2006. 81(3): p. 280-5.

- Frye, A.W. and P.A. Hemmer, Program evaluation models and related theories: AMEE guide no. 67. Med Teach, 2012. 34(5): p. e288-99.

- Schuman, E., Evaluative Research Principles and Practice in Public Service and Social Action Progr. 1968, New York: Russel Sage Foundation

- Bickman, L., The functions of program theory. New Directions for Program Evaluation, 2004. 1987: p. 5-18.

- Wholey, J., Evaluation and Effective Public Management. . 1983, Little Brown.

- Measuring Program Outcomes: A Practical Approach ed. U.W.o. America. 1996.

- Logic Model Development Guide, ed. W.K.K. Foundation. 2004.

- Glynn, M.K., et al., Strategic Development of the Public Health Workforce: A Unified Logic Model for a Multifaceted Program at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Journal of public health management and practice : JPHMP, 2019.

- Wu, H., et al., Using logic model and visualization to conduct portfolio evaluation. Evaluation and Program Planning, 2019. 74: p. 69-75.

- Tackett, S., J. Grant, and K. Mmari, Designing an evaluation framework for WFME basic standards for medical education. Med Teach, 2016. 38(3): p. 291-6.

- Railer, J., et al., Using outcome harvesting: Assessing the efficacy of CBME implementation. J Eval Clin Pract, 2020.

- Van Melle, E., et al., A Core Components Framework for Evaluating Implementation of Competency-Based Medical Education Programs. Acad Med, 2019. 94(7): p. 1002-1009.

- Melle, E.V., Using a Logic Model to Assist in the Planning, Implementation, and Evaluation of Educational Programs. Acad Med, 2016. 91(10): p. 1464.

- Van Melle, E. Program Evaluation for CBME: Are we making a difference? . in The International Conference on Residency Education. 2016. Niagra Falls, Ontario, Canada.

- Campbell, J.R., et al., Building Bridges Between Silos: An Outcomes-Logic Model for a Multidisciplinary, Subspecialty Fellowship Education Program. Acad Pediatr, 2015. 15(6): p. 584-7.

Annotated Bibliography

1. McLaughlin, J.A. and G.B. Jordan, Logic models: a tool for telling your programs performance story. Evaluation and Program Planning, 1999. 22(1): p. 65-72.1

This paper was one of the first to outline in detail, the practical applications of the Logic Model. It was intended to explain to program managers in the public and private sectors how to measure and evaluate a business program and how to use that knowledge to improve a program’s effectiveness. By utilizing clearly outlined figures and tables, these authors provided a detailed explanation on how to build a Logic Model for business managers.

2. Logic Model Development Guide, ed. W.K.K. Foundation. 2004.9

This Kellogg foundation document outlined important definitions of the Logic Model as a method of program evaluation. “The program logic model is defined as a picture of how your organization does its work- the theory and assumptions underlying the program. A program logic model links outcomes (both short and long term) with program activities/processes and the theoretical assumptions/principles of the program.”

3. Otto, A.K., K. Novielli, and P.S. Morahan, Implementing the logic model for measuring the value of faculty affairs activities. Acad Med, 2006. 81(3): p. 280-5.3

Otto et. al in 2006 published the first landmark article in Academic Medicine suggesting the use of logic models in medical education. They suggested use of logic models for measuring the contribution of faculty affairs and development offices to the recruitment, retention and development of a medical school’s teaching faculty in efforts to reward faculty for teaching. They nicely review the structure of a logic model overall and give an example of its use in a visual format with a comprehensive associated list of components in each category. Use of the logic model is suggested to facilitate the process of thinking through the entire faculty development process.3

4. Frye, A.W. and P.A. Hemmer, Program evaluation models and related theories: AMEE guide no. 67. Med Teach, 2012. 34(5): p. e288-99.4

AMEE Guide No. 67. This paper takes a broader view of various program evaluation models. It is useful because it compares and contrasts several different models. In addition to the Logic Model, it also discusses the experimental/quasi-experimental model, the Context/Input/Process/Product Model (CIPP model), and Kirkpatrick Model. It delves into the strengths and weaknesses of each type of model and how they can be applied to Medical Education. The authors in this paper provide a good description and analysis of each of the four essential elements of the Logic Model. It provides various medical education centered examples of each of these elements.4