4-4 Research Project Logistics: Project Management and Study Schedules

Mark Lee

Overview

We’ve all been there at some point in a project where we wish we had planned better how we were going to approach this project, and been more proactive at the start. Whether it was in high school – remember those “dreaded” high school projects – or even now as mid-career scientists managing a research project that has just completely unravelled or stalled. It had nothing to do with the quality of the idea, nor necessarily the volume of work and multitude of components that needed to be managed. Rather, it was the way you and/or your team approached the process, by choice or by happenstance.

As someone who has had these experiences, I’m reminded how important – yet rarely – we talk about the process. How did we get here? How come this worked well? How come this didn’t work for our team? We often undermine the skill required to navigate and manage the logistics of a project. Yet, no matter how great an idea, things can easily go awry if we don’t dedicate time to discuss the progress – the “HOW” that gets us from start to finish. The hope of this chapter is to provide some tips and tricks for anyone who is a part of a research team on how to approach the process of research project management.

Key Points of the Chapter

By the end of this chapter, the learner should be able to:

- Discuss the various considerations when navigating a research project

- Apply different strategies and tools when managing research projects

Vignette

A rare lull on a rainy autumn Friday afternoon. It’s been a week of back-to-back meeting days for Dr. Rayleen Yang, and as she looked at her calendar and their seemingly never ending to-do list, a wave of angst overwhelms their mind.

“Deep breath, Ray, deep breath”, she reminded herself.

It had been almost five years since Dr. Yang had first started as an assistant professor position with the Rehabilitation Sciences program as an education scientist. The first few years felt relatively smooth sailing, she had been mostly publishing some previous work and starting a handful of new studies. However, between current project delays, new collaborations on papers, and then successful grants that required getting started, she was starting to wonder how she would ever manage to juggle so many projects!

Looking out the window, Rayleen was reminded of words she had heard often during grad school: “Trust the process.” As much as she trusted she could get everything done, she are starting to wonder if there’s a better way of approaching projects to optimize efficiency – a question she’d never really had to stop to ask themselves.

Deeper Dive into this Concept

Organization skill seems to be one of those generic aptitudes frequently thrown out in interviews and performance reviews, often talked about in this binary of “you have it” or “you don’t have it”. While some individuals may be ‘naturally’ organizationally-minded, I never found these distinctions helpful as it misses the point that organization is something that we all can actively work on and that has some context specificity to it (i.e. some strategies will work in some situations and not others).

Functionally, the goal of discussing research project management is not to see organization as some general skill, but rather helping people explore and build strategies and tools to stay organized. It’s easy to say “stay organized” – but what does that actually mean in the context of research project management? What are some particularities of research in the health professions education (HPE) world? We provide some thoughts on this matter that complement the existing resources in this chapter. Throughout, we’ve highlighted some questions to ask you and your team, key insights, and additional considerations that weren’t particularly discussed in the other chapters.

Understanding the project

Scope, Outcomes, and Deadlines

Before you talk about managing a project, you really need to understand the scope and scale of your project. Take a listen to these podcasts as they speak to project management.

In Episode 9 and 10 of the HPER podcasts (listed above), Drs. Teresa Chan, Larkin Lamarche and Mark Lee speak to great lengths on this topic; some key questions to ask yourself include:

- What are your project objectives? What do these objectives look like in terms of deliverables?

- Does this project have multiple partners, sites and/or phases? Check out the paper by Schiller et al. (3) on multi-institutional project management.

- How will the methodology impact the task list needed to be completed before or during the study?

- Taking the typical progress of a research study, is there anything that will be similar and/or different for the context of this particular project?

At the onset, it’s valuable to lay these components out explicitly, as your outcomes and deadlines will be impacted by your answers to these questions. With project objectives, being able to outline the deliverables can help you get a sense of your task list. These deliverables can look like the final report, published paper, but also deliverables within the steps of a research study (e.g. cleaned datasets, de-identified transcripts). This will not only help you accurately establish a realistic timeline, but also avoid forgetting steps down the road.

Assess if the scope is feasible given the parameters of the project (e.g. timeline, resources). If not, take a moment now to figure out what additional support you might need.

Understanding your Institution

Academia is not without its volume of organizational bodies that tend to be involved throughout the research process. This could include: research ethics boards (REBs), financial approvals for grants, and department/program-level approvals. In HPE, we often will also require approvals from the chair of the student programs, from which our participant pool is sampled.

The hope is that you’re able to send the same documents (e.g. protocols, instruments) to all organizations for review. That being said, keep in mind that different organizational bodies may require specific framing based upon their interests. For example, student programs may be more interested in understanding how your research will pull on the resources of the program and take students away from their studies. How might you frame your project so the program fully understands what you’re asking from student participants?

Consider building rapport with individuals in these organizational bodies. It often is helpful to have a go-to person in each organizational body for nuanced and/or urgent matters.

In the context of HPE research, a valuable consideration when applying for ethics is whether your project falls under quality improvement and/or program evaluation. Some institutions will have a separate approval process for these projects; some even have separate approval for education research projects regardless of intent. These processes will often be shorter and quicker than going through a full ethics review, which may be a consideration based on the scope and deadlines of the project. That being said, there may be implications with publication as some journals require studies to have gone through a full ethics review. Read the fine print before proceeding through this route. See Chapter 4-1 for a more in-depth review of this topic.

Timeline, Roles and Expectations

Remember when you explicitly laid out all the components of the project: objectives, deadlines and outcomes? The next step is to pull up that list and see if it requires further elaboration. Take a look at your tangibles and see if there are any tasks that require breaking down further. How granular you go will really depend on your experiences with this process (the newer, the more granular). The importance of this step is that it recognizes that if this is your first time completing a task (e.g. ethics), it may require unpacking all its subcomponents.

Don’t re-invent the wheel

Have templates for similar processes (e.g. ethics, grants, institutional forms). Something might take half the amount of time simply by having existing templates to work from. This idea was previously been mentioned in Chapter 3-1.

With all your components, you can now start building a timeline. Usually there is a “end-date/time” to projects (e.g., when you need to submit a final report to a granting agency).

If not, it’s still probably helpful to have some project end date (e.g. when do we want to have a finalized paper to submit). Working backward from that end date, you can start to approximate when the various pieces of the project need to be completed. Gantt charts (5) can be a great resource to visualize your tasks relative to the timeline.

Exercise: Some Questions to Consider about your Timeline

- How long will data analysis take? Will this process occur iteratively and require analysis during data collection? Based on the volume of data, how long might it take to clean the data so that it can be analyzed?

- Are there timelines for review processes by organizational bodies (e.g. ethics, departmental approvals)? Do these organizational bodies meet regularly? If so, when do you need to have documents submitted to them for review?

- How long will it take to write? If you’re writing in teams, how much time will you allocate for internal review?

Always allocate buffer time for any review processes, even signature requests – this step can take longer than you anticipate.

If you are working with a team – in HPE research, this is probably a given – check to see that everyone is on-board with the timeline. As Dr. Lamarche and Chan mention in episode 10, if a step is new to you, it might also be helpful to reach out to individuals outside your team for advice. This may be another researcher who has completed a study like yours in the past, or even a research support staff who has deep insights on completing specific processes. They may have valuable insights to share to make the process go smoother. Consider consulting Chapter 4-2 which covers the topic of collaborative writing in more depth.

Roles and Expectations

When working in teams, it is imperative that you discuss roles and expectations as a group, especially early on in the project. The phenomenon of diffusion of responsibility is a real concern in groups, and when everyone is busy and balancing many other projects, it’s easy to assume another team member will pick up the slack. It’s important to explicitly talk about roles and expectations now rather than later, when things may have fallen through the cracks. For research projects that you’re hoping to publish, consider who will be part of the authorship team and what contributions they will need to make in order to meet ICMJE authorship criteria (6). Having this conversation at the start will help mitigate any awkward conversations later on when stakes might be higher.

Exercise: Some Questions to Consider about your Team

- Will specific individuals lead different parts of the project? How might this impact the authorship list?

- Given the strengths and availability of the team members, how might we optimally lean on each team member to complete this project?

- Do we need extra hands? Is there value to hiring research staff (e.g. research assistant, research coordinator) to support this project? What skills might you be looking for these additional individuals?

- If it’s a very collaborative team, how do you ensure pieces don’t get missed?Additional Consideration: If you are leading a team for the first time, Gorsky et al. (2016) has a list of project leadership principles that might be valuable to review.

Project execution & monitoring

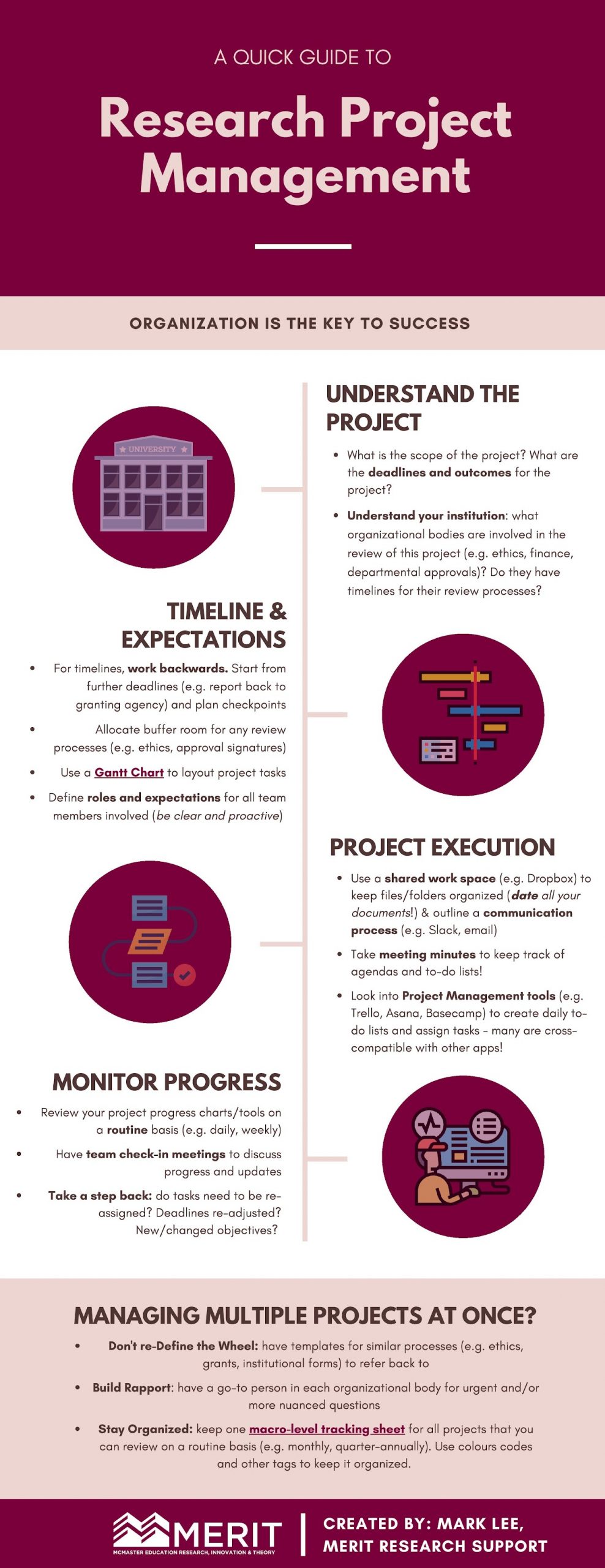

With tasks outlined, roles delegated, and expectations discussed, it’s time to start the project itself. But wait – how will you keep track of all these moving parts and keep each other in the loop? As listed in the research project management infographic, there are three things worth establishing:

- Shared work space and communication platform:

- Where will you keep all your files? Consider the value of folders to keep documents organized and make it easier to retrieve documents.

- On what platform will you stay in communication with your team? Emails might be great for providing updates, while communication platforms like Slack, Microsoft Teams, might better suit back-and-forth conversations. Google Docs messages may also link your team in a shared writing canvas that allows for communication via margin comments as well.

- Meeting minutes:

- We often underestimate how valuable it is to have a record of decisions and notes to refer back to. How many times have you had to revisit the same conversation because your team has forgotten what you had decided in the last meeting? Or, a team member had some great insight for the discussion section of a paper during data collection, but no one remembers it now?

- Additional Consideration: Consider taking notes every meeting, whether throughout a meeting or at the end by summarizing the main takeaways and next steps at the end of each meeting. Could you assign someone to do this (e.g. research staff, students, junior team members)?

- Project management tool:

- With more nuanced projects, it might be worth exploring a project management tool to keep track of to-do lists and assigned tasks. While keeping a running document might be the simplest form, these project management tools not only allow for cross-compatibility with other apps (e.g. Google Documents), but can also do automatic notifications and reminders. There are many free options nowadays, so don’t be afraid to try something new!

Again, all of these points and a very useful summary of collaborative tools are more fully discussed in the HPER Chapter 4-2 (Working Collaboratively).

Monitor Progress

With the project underway, it’s always valuable to routinely review the progress, especially if you’re the lead or organizer. This is your moment to take a step back and look at the project as a whole. Are tasks moving along? Are the established deadlines still realistic? Any new objectives or ones that require modification? If you’re navigating multiple projects concurrently, it might be valuable to create a tracking sheet so you can look at your projects all together (see the Research Project Management infographic for a link to an example Excel sheet).Proactively set up team meetings. Even if there are no imminent deadlines, I have found it helpful to set up regular meetings for projects, or to set up the next meeting at the end of a meeting. How often has this happened where you want to meet to discuss a semi-urgent matter but because most people’s schedules are booked to the max, you’re looking at dates in a month’s time?

Conclusion

It is important to build a tool belt of strategies that you can pull from when you need to in the context of learning. Project management is no different. The tool belt analogy acknowledges that sometimes you will be able to use tools you already have. However, sometimes you’ll need to go out to find new tools to add to your belt. Trust yourself and the tools you’ve gathered so far… but don’t be afraid to try something new and re-evaluate when necessary. Remember, it’s all about the process!

Key Takeaways

ABCDE’s of Research Project Management:

- Act proactively – Taking the time at the beginning of projects to check-in and figure out how to best organize this project for the team will help mitigate forgotten tasks and project delays. Whether it’s a project management tool or more simply an ongoing document, find a way for you and your team to stay on top of your project.

- Break it down – Sometimes projects or tasks will feel so large to the point of overwhelming. Break the task down into discrete tangible sub-tasks. Work from those sub-tasks to keep on top of all the moving parts.

- Clear Communication and Expectations – Clearly establish communication mechanisms for the team, along with roles. Who is responsible for which tasks? How often do you need to check-in as a team to ensure the project is moving along

- Debrief the process – Make it a habit to debrief the process throughout and at the end of projects, independently and with your collaborators. What worked? What could have been done differently to optimize group and task goals?

- Explore something new – It’s easy to get stuck in our ways, even when it isn’t proving to help us stay productive. Don’t be afraid to try something new – a different project management tool, new way to discuss roles and expectations.

Also check out this amazing summary infographic of all the content from this chapter that is available here!

Vignette Conclusion

The cherry tree outside their window is in full bloom.

“Something so refreshing about the spring.” Dr. Yang thought to themselves.

Although it had been a busy few months, Dr. Yang noticed that her mind felt less cluttered and had been feeling a lot more manageable lately since she last did a self check-in. When things were becoming harder to navigate, Rayleen had reached out to some mentors for support who provided her with some considerations and tools to stay on top of their work. On top of using Trello to manage their projects with fellow collaborators, she had learned to break tasks down to make things feel more feasible, which has made projects more achievable. She had also been able to bring on board a research assistant to support two of their projects, who has been a significant help keeping the ball rolling.

While there are some things that can still be made more efficient – “Why are my files in so many different apps?!” – Dr. Yang would make it a point to do these check-in’s quarter-annually to see how she can continue to build on the strategies to support their shared research endeavours.

References

- Gorsky D, Mann K, Sargeant J. Project management and leadership: practical tips for medical school leaders. MedEdPublish. 2016 Nov 17;5. https://www.mededpublish.org/manuscripts/651

- Huggett KN, Gusic ME, Greenberg R, Ketterer JM. Twelve tips for conducting collaborative research in medical education. Medical teacher. 2011 Sep 1;33(9):713-8. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2010.547956

- Schiller JH, Dallaghan GL, Kind T, McLauchlan H, Gigante J, Smith S. Characteristics of multi-institutional health sciences education research: a systematic review. Journal of the Medical Library Association: JMLA. 2017 Oct;105(4):328. doi: 10.5195/jmla.2017.134

- Schlegel E, McLeod K, Selfridge N, Practical Tips for Successful Implementation of Educational Innovations: Project Management Tools for Health Professional Educators ‘, MedEdPublish, 2018; 7(2); 36. https://www.mededpublish.org/manuscripts/1581

- Petersen PB. The evolution of the Gantt chart and its relevance today. Journal of Managerial Issues. 1991 Jul 1:131-55.

- International Committee of Medical Journal Editors. Defining the role of authors and contributors. 2021. ICMJE. http://www.icmje.org/recommendations/browse/roles-and-responsibilities/defining-the-role-of-authors-and-contributors.html

Summary Infographic